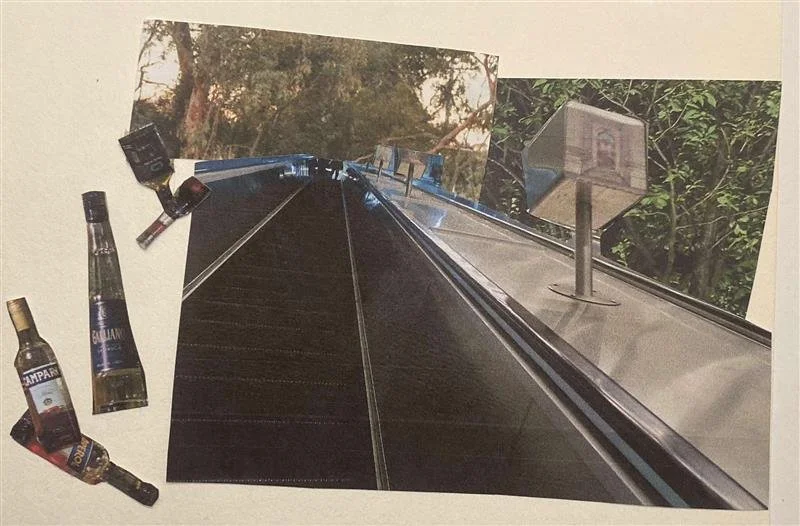

The city funnel

Picture by Amelie Vorchheimer

Observational writers journal, city, tram, July 19th

During summer, the city traps the warmth, it holds it; the concrete whispers, tickling you with its hot, sour breath, a heatwave halitosis. Light lingers, and we await the sweet relief of night. In winter we demand summer back; ice radiates off glass doors and metal railings, and the cold corners of streets where gale-force winds break against you. People pat their pockets, checking Mother Nature hasn’t mugged them; note to self, stand behind someone when possible.

Australians like to think they’re rough and rugged, deterred by very little, but there is only about three degrees that determines whether Melbournians come out to play or hunker down. The colour of the sky matters too; sheets of moribund grey means work, get-in-get-out. But if that baby blue makes an appearance, broken up by cotton-white pillows, then twelve degrees is not so bad, one might even have their flat white to go. Lululemon and a brisk walk through the suit district, nicely offset by junkie district, that’s for days like today.

When night falls, the city’s bowels empty; we are the shit that tracks through it, and Flinders Street is the taint, no doubt. The studious end of Swanston Street withstands this chill; deadlines pay weather no mind. Satchels and backpacks trek towards the hive of public transport, there’s no excuse for them to bump into one another at this time of night, and yet they do: pavement pushers. A rolodex of scent pumps out of restaurant vents and melds together, creating one super-international cuisine: experimental gastronomic fusion gone wrong.

Track-works mean trams are overpopulated – more than usual, if that were possible – and as the 86 burrows in, with a prickly squealing trailing behind it, the late-for-dinner arrivals fight to press themselves up against the doors. Those departing wade through the thoughtless arrivals, clotting the entry. Inside, passengers are contorting to allow newcomers, clutching their bags and compressing their bodies, white-knuckling handrails as they brace for movement.

Chatter commences and some voices can be heard more than others, certain pitches are able to break through the overall clamour. A boisterous man in a thoughtfully tailored suit can be heard interviewing his female companion. You can hardly make out her docile responses, but you can hear his – crisply – and put together what she might have said. The whole tram gets to know what the man enjoys in bed, and his woeful attempt at a balanced review of a mutual friend. Some passengers have plugged their ears with music and can’t hear him, others are pretending.

People play snap with their eyes, casing the carriage for empty seats or other passengers beginning to map a path to the doors. It must be a hell ride for those hanging on for the last stop: Bundoora, a place now stained by that man who robbed that girl of her life. Maybe they don’t think about it, and maybe it gets peaceful towards the end as commuters trickle off.

A dope-sick man is keeled over, taking up one and a half seats. A girl condenses herself to fit beside him: brave, or desperate. On the nod, his skin glistens with sweat and is tinted a shade of sickly lilac. He too is clutching his belongings, intermittently losing grip of his phone and swaying with the tram. More people pretend not to see him as he looks up, adjusting his cap and scoping his surroundings before collapsing back into his bag. The suits wedge their briefcases a little tighter between their legs.

These lights are cold and cruel, it’s no easy feat to rest peacefully here. Recycled air blows through the carriages, and a low-level buzz can be heard beneath it all, it’s what keeps the whole operation running; power is the lifeblood of the city.